Cassini Spacecraft Tracks Venus Transit From Saturn

By Space Coast Daily // December 27, 2012

First Such Observation From Beyond Earth Orbit

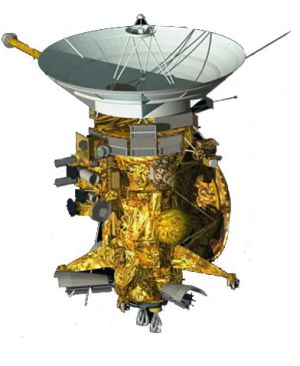

BREVARD COUNTY • KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLORIDA – For seven years, a mini-fridge-sized instrument aboard NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has reliably investigated weather patterns swirling around Saturn, the hydrocarbon composition of the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan, the aerosol layers of Titan’s haze and dirt mixing with ice in Saturn’s rings.

But this year the instrument — the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIMS) – has been testing out some new telescopic muscles.

Last Friday, the spectrometer tracked the path of Venus across the face of the sun from its perch in the Saturn system.

Earthlings saw such a transit earlier this year, from June 5 to 6.

But the observation was the first time a spacecraft has tracked a transit of a planet in our solar system from beyond Earth orbit.

Cassini collected data about the molecules in Venus’s atmosphere as sunlight shines through it. But learning about Venus actually isn’t the point of the observation.

Other tasks

Scientists actually want to use the occasion to test the VIMS instrument’s capacity for observing planets outside our solar system.

“VIMS has worked so well at Saturn so far that we can start thinking about other things it can do.” Phil Nicholson, VIMS team member based at Cornell University in New York

“Interest in infrared investigations of extrasolar planets has exploded in the years since Cassini launched, so we had no idea at the time that we’d ask VIMS to learn this new kind of trick,” said Phil Nicholson, the VIMS team member based at Cornell University in New York, who is overseeing the transit observations. “But VIMS has worked so well at Saturn so far that we can start thinking about other things it can do.”

VIMS will be able to complement exoplanet studies by space telescopes such as NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. VIMS scientists are particularly interested in investigating atmospheric data – such as signatures of methane — from far-off star systems in near-infrared wavelengths.

The pointing has to be very accurate to get one of those extrasolar planets in VIMS’s viewfinder, but the instrument has had lots of practice pointing at other stars. Earlier this year, VIMS obtained its first successful observation of a transit by the exoplanet HD 189733b. Scientists want to improve these observations by reducing the amount of noise in the signal.

Flexibility

In April, VIMS demonstrated another kind of flexibility by turning its eyes to the warm fissures slashing cross the surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. VIMS is particularly good at taking thermal data in temperatures around minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit (200 kelvins). So while it is good at tracking hotspots and turbulent clouds on Saturn, VIMS is generally unable to detect thermal emission from Titan, the icy satellites or the rings, since their temperatures are much colder than that.

But the fissures on Enceladus, which scientists have called tiger stripes, are just hot enough for VIMS to detect heat coming from them.

“For the first time, we were able to see that the jets coming from the surface of Enceladus originated in very small, very hot spots,” said Bonnie Buratti, a VIMS scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “This new observation is good evidence for liquid water underneath the surface.”

VIMS is one of 12 instruments on Cassini, which launched in 1997 from the Kennedy Space Center and began orbiting Saturn in 2004.

“We built Cassini to be hardy, and we’re pleased that the spacecraft has been weathering the extreme conditions of the Saturn system remarkably well,” said Robert Mitchell, Cassini program manager at JPL. “It isn’t too tired to try something new.”

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.