‘Ghost Guns’ Battle Raises Question of What Counts as a Firearm

By Space Coast Daily // September 14, 2020

the weapon used by Patrolman Andrew Moye Jr.'s shooter had no serial number because when it was sold, it was not technically a gun

California Highway Patrolman, Andrew Moye Jr., was killed by a gun the government did not know existed.

State law in California requires all firearms to be registered and given a serial number. Serial numbers allow investigators to trace guns used in crimes, and this information can lead police to the gun owners, and sometimes to major sources of illegal weapons.

However, the weapon used by Officer Moye’s shooter had no serial number because when it was sold, it was not technically a gun.

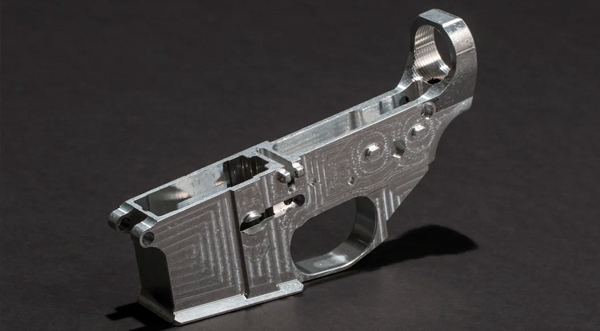

“Ghost guns,” as weapons like this are known, frequently begin as premade gun kits. At the time the kit is sold, it is just a set of parts, with only the potential to become a gun later on. Therefore, registration laws do not apply, and neither do background checks or waiting periods. Increasingly ubiquitous 3D printers are another common source of ghost guns.

In 2019, California passed AB-879, a bill born from the joint efforts of state politicians and law enforcement officers from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. AB-879, signed by Governor Gavin Newsom, expands background check requirements to apply to unfinished gun parts. Starting in 2024, the law will also ban anyone in California from selling gun kits without a license.

California is one of only five states (plus the District of Columbia) to have any legislation targeting untraceable guns.

“I believe the reason more jurisdictions don’t have laws about untraceable weapons is that it’s difficult to get people to agree on the boundaries of such a policy,” Attorney Jo-Anna Nieves of The Nieves Law Firm, APC said. “In California, it’s legal to build your own gun as long as you don’t sell it or give it away. Should it be against the law not to register your parts? If it is, should it be illegal to own unregistered parts even without putting them together? At what point does it become a firearm? It turns into a Ship of Theseus sort of problem.”

The Ship of Theseus, a philosophical conundrum first posed by Thomas Hobbes, imagines that the mythical Greek hero Theseus gradually replaces each part of his ship until none of the original parts remain. Does he now have a new ship? Or is there some essential “shipness” that persists regardless of its components?

Far from an airy debate for philosophers, the question of what makes a firearm a firearm is the crux of the dilemma for lawmakers trying to cut down on ghost gun sales. California’s AB-879, for example, regulates frames and receivers, critical connective parts that make a gun’s more active components work together.

Those in favor of gun control argue that there is nothing an AR-15’s lower receiver can be used for other than becoming part of a gun. Those opposed counter that the government infringes on civil liberties by surveilling the purchase of an essentially harmless piece of metal.

Different jurisdictions have different answers to the question of what counts as a firearm. Washington State defines a firearm as “a weapon or device from which a projectile or projectiles may be fired by an explosive such as gunpowder.” It explicitly excludes flare guns and “powder-actuated tools” used for construction.

Federal law is close to the California definition, including frames and receivers under the umbrella of firearms, but goes farther by also including mufflers and silencers.

Complicating matters, both California and the federal government also define “destructive devices” like grenades as firearms, even though they share nothing in the way or structure. Both law codes exclude antique weapons, even those that do share structure. It does, indeed, get complicated fast.

At the heart of the question of what makes a gun a gun is whether the government’s foremost responsibility is to guarantee freedoms or to protect lives and property. Law enforcement officers and U.S. representatives are working on a federal bill modeled on California’s AB-879, titled the “Ghost Guns Are Guns Act,” that is sure to add new weight to all these ancient debates.

The officers, politicians, and voters working to counter the rise of ghost guns want to keep guns out of the hands of dangerous criminals like Officer Moye’s killer. Yet their opponents fear that the biggest victims of the Ghost Guns Are Guns Act will be hobbyists who view building guns like others would think of building a ship in a bottle.

If nothing else, the gun control debate reveals to us the basis of a reliable legal code: a firm philosophical grounding and strong definitions.