Red Sox Gave Robinson First MLB Tryout In 1945

By Space Coast Daily // April 15, 2014

THIS YEAR MARKS THE 70th ANNIVERSARY OF THE LITTLE KNOWN FIRST MLB TRYOUT FOR BLACK PLAYERS

Baseball drama “42,” a biographical sports film written and directed by Brian Helgeland about the life of major league baseball icon Jackie Robinson, who under the guidance of Brooklyn Dodger team executive Branch Rickey became the first black player in the major leagues 70 years ago, was released last year and took home a win at the movie box office.

Jackie Robinson Day Is April 15

The movie chronicles Robinson’s rise from the Negro Leagues to the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947.

When Rickey raised the issue of considering bringing African American ball players into the major leagues with the Dodgers’ top brass in the early 1940s, he was told he could proceed “as long as his purpose was not a crusade but the economics of strengthening the roster and widening the fan market.”

Jackie Robinson’s legacy was memorialized on April 15, 2011, by fans, players and Major League Baseball, marking the 70th anniversary of the Hall of Famer breaking baseball’s color barrier.

On April 15, all uniformed personnel at 15 different ballparks will be wearing Jackie’s retired No. 42.

Red Sox Take A Look At Robinson In 1945

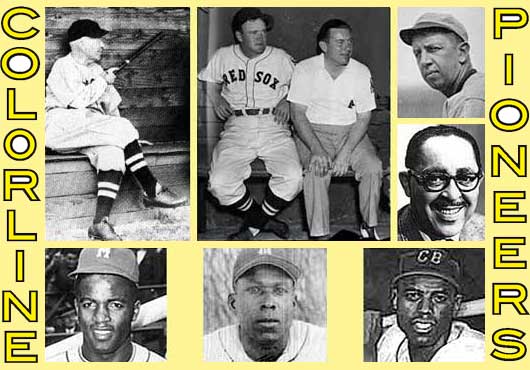

Ironically, Rickey was not the first to offer a tryout to Jackie Robinson. Robinson’s first tryout was the result of lobbying by Wendell Smith, black sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier and unrelenting champion of professional sports integration, and Boston city councilman Isadore Muchnik, who had threatened to revoke the Red Sox’ permit to play Sunday games at Fenway Park unless they granted a tryout to black players.

The Sox agreed, and Smith chose two stars from the Negro League, Philadelphia Stars shortstop Marvin Williams and Cleveland Buckeyes outfielder Sam Jethroe, and ex-UCLA running back Jackie Robinson.

In retrospect, it is remarkable that Robinson was even invited to the tryout, but turned out to be a very shrewd move on the part of Smith. Although a remarkable athlete, Robinson had not played organized baseball at any level for six years. (In his last try at the sport, in 1940, Robinson had batted .097 for UCLA.)

Although he was about to begin his first season with the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League, there was no reason that anyone in the spring of 1945 should have expected him to succeed at baseball. In the years since giving up baseball, Robinson had spent his time playing professional football and basketball, serving in the Army during World War II, and coaching a college basketball team in Texas. The fact that his name even came up as a candidate for the tryout was a tribute to his tremendous athleticism.

The tryout at Fenway Park on April 16, 1945 – two years before the color barrier was broken – was supervised by four Hall of Famers – Hugh Duffy, a Red Sox coach; Joe Cronin, the manager; Eddie Collins, the general manager; and transplanted Southerner, Tom Yawkey, the owner. Immediately following the tryout, all four tried to dodge responsibility for evaluating the players. Yawkey’s public stance was that decisions regarding players needed to be made by his baseball people. Collins, the GM, was unable to attend the tryout “because of a previous engagement.”

Cronin, the manager, attended the tryout but said that any comment would have to come from Duffy who supervised the workout. Duffy, the 78-year-old coach, said the players were “fine fellows” who played “all right,” but he couldn’t make a decision about their ability after only one workout. The tryout proved to be a sham and the players never heard from the Red Sox again. It was the first and last appearance at Fenway Park for all three players. The political requirements had been satisfied, and the three players were left exactly where they had started: with no reasonable hope of ever playing major league baseball.

Wendell Smith Key To Rickey-Robinson Alliance

Wendell Smith, a journalist for the Pittsburgh Courier, played a central role in bringing about integration in major league baseball. Smith, who had previously gone so far as to (unsuccessfully) ask President Roosevelt to intervene and desegregate baseball by executive order, was incensed by the patronizing attitude of the Red Sox and Major League baseball.

Undeterred from his crusade, he continued a blistering editorial campaign that got both the black and white communities talking when he compared Nazi Germany’s treatment of minorities to America’s insistence on segregated ball leagues. In another high profile article, he interviewed major league players and managers, soliciting their views on playing alongside blacks. His results were overwhelmingly positive for desegregation.

Although the Boston try-out was a farce, Smith gained credibility with key baseball operatives, and it was he who recommended Jackie Robinson to Branch Rickey as the man most suited to break the color line in professional baseball. Robinson, of course, went on to break Major League baseball’s color line and earn the Major League Rookie of the Year award in 1947.

Sam Jethroe was the first black man to play Major League baseball in the city of Boston, breaking in with the Braves and winning the National League Rookie of the Year in 1950.

It was 1959, 14 years after the politically motivated sham tryout, when the Red Sox finally fielded a black player.

GREAT ARTICLE. i HAD NOT READ THAT BEFORE.

Jackie Robinson was/is my Dad’s idol! And today is my Dad’s 73rd Birthday!!!