Conch Farming Could Catch On In Brevard

By Lauren McFaul // April 16, 2012

Business

BREVARD COUNTY • COCOA BEACH, FLORIDA – Pawn of overfishing and habitat destruction since the 1960s, emerging technology might be a game-changer for Florida’s Queen Conch and give rise to a new conch farm industry in Brevard County.

The popular, edible sea snail inhabits the shallow waters of 36 countries that ring the Caribbean.

Even though it has been farmed commercially since the 1980s, wild populations remain at risk, despite 1973’s Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species Act and an outright fishing ban in U.S. waters since 1986.

Annual production of conch meat from treaty countries is about $60 million, according to the CITES World newsletter, but Florida’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute may prove Strombus gigas, or Queen Conch are not just for chowder anymore.

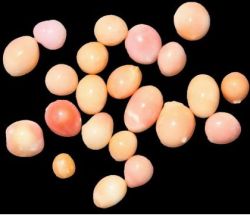

Queen conch pearl gemstones loom on the horizon as a new revenue producing source, yet up to now the stones have been a rare by-product of food industry and the odds of finding a naturally-occurring conch pearl is 10,000 to 1.

Precious few of those meet the American Gem Institute standards for quality.

And finding a matched pair? Less likely still, say AGI experts.

If discovered, the conch pearl pairs may be valued at more than $1,000 per carat.

Once held in royal collections — most famous is the pink pearl brooch worn by Mary, Queen of Scots — the stones enjoyed popularity in Victorian and Edwardian eras.

A few Art Deco examples exist, but the conch pearl has remained an odd ball on the precious stone scene, although Modern Jeweler magazine reports the Italian firm Damiani sold Brad Pitt one of the gems a few years ago.

Conch Pearls aren’t actual pearls, but built from calcium carbonate, a mineral similar to lime.

Kidney stones

The process and product of their formation has been compared to kidney stones in humans.

They occur when an irritant lodges between mantle and outer shell and gives L’ Grande Dame the gout.

Their colors mimic the sunset-and-sand hues of the conch’s shell.

And while they don’t have the layers of lustrous nacre of bivalve stones, conch pearls do have what is known as “flame,” — thin whorls of contrast colors deposited as the snail meanders along, sliding against her spiral shell.

As for culturing the stones, anatomy has been destiny. Methods for reaching far into the shell injure the sea animal.

Gentler touch

Dr. Megan Davis-Hodgkins, HBOI’s Director of Aquaculture and Stock Enhancement, seems to have a gentler touch.

She and former HBOI staffer Héctor Acosta-Salmón have cultured more than 200 of the pearls to date and HBOI is in the process of patenting the technique, with an eye toward creating a new industry for Florida and maybe right here in Brevard County.

To that end, Florida Atlantic University, the parent of HBOI, has partnered with Vero Beach firm Rose Pearl, LLC.to license and commercialize the technology.

Since the mollusks have been known to range as far north as the Indian River Lagoon, who knows?

Might this not be the next big thing in backyard gardens along some of Brevard County’s waterfront homes?

Not likely very soon, Davis-Hodgkins said.

“Conch prefer oligotrophic waters (clear and full strength seawater), whereas the Indian River Lagoon is estuary water, with brackish salinity and not clear.”

Davis-Hodgkins has been active in conch mariculture since 1981 and co-founded the first conch farm in the Turks and Caicos Islands.

She has been an educator and researcher at both FAU and HBOI in the years since.

Water quality

Beyond the lagoon water’s salinity problems, conch pearl farming may prove difficult for Florida and in Brevard, with the chief drawback being water quality.

“In general there are large areas (of the Caribbean) that are clean enough for conch nurseries” Davis-Hodgkins said. “But some areas where the conch nurseries are close to the land, where there has been a lot of human impact, may not be ideal nursery grounds.”

Given the added value, conch mariculture is likely to become more common in the 21st century.

“Undoubtedly”, said Manuel Marcial de Gomar, President of Emeralds International, LLC., one of few U.S. firms which specialize in conch gemstones.

Marcial has collected conch pearls since 1959 and features them in his original designs in his stores in Key West and Charleston, S.C.

“The HBOI success will incentivize Queen conch pearl culturing,” he said. “Much will depend on the structure of expansion policies determined by HBOI, whether by licensing others or retaining ownership. HBOI’s success will impel other countries to follow suit.”

Hopefully, increased conch mariculture will help protect wild stock and deep water ‘refuge’ populations, according to HBOI educational material.

On the other hand, increased interest in conch pearls may spur increased poaching.

“In this question lies the heart and soul of the future for conch pearls,” Marcial said. “CITES has excellent laws in place for the protection of the queen conch. The danger lies in the lack of adequate enforcement of those laws by the governments of signatory nations.”

Changing attitudes

Conch meat is primary to the search for conch, but that may be changing in the minds of boat captains as the values of the elusive and very rare conch pearl soar upwards.

“We can only hope that CITES signatories respect current legal safeguards,” Marcial said. “The success of conch pearl nurseries will depend greatly on the accurate certification of their production.

“The collapse of Queen conch pearl fisheries is imminent. The situation is urgent,” Marcial said. “Illegal fishing of the Queen Conch has reached a point where it’s no longer sufficient to just bark, it’s time to bite the offenders, confiscate their vessels, impose fines and jail time.”